Was reading the new Oxford collection on conspiracy theory (quite an impressive collection, can be bought here) and noted that one of the articles dated the term conspiracy theory back to the 1870s. It’s not central to the author’s argument, but it’s not trivial either. The author sees the term as coming out of crime, and then navigating to politics:

Such considerations encourage a more systematic approach. By consulting databases that have digitized American newspapers from the nineteenth century, it is possible to gain an appreciation of how theory as a term made inroads into the discourse of crime. Thus, a search of the database America’s Historical Newspapers identifies the following dates as the earliest mention for conspiracy theory and other terms built on the template (crime x + theory):

murder theory (1867)

suicide theory (1871)

conspiracy theory (1874)

blackmail theory (1874)

abduction theory (1875)

From Conspiracy Theory: The Nineteenth-Century Prehistory of a Twentieth-Century Concept from Conspiracy Theories and the People Who Believe Them (p. 62). Oxford University Press. Kindle Edition. .

This is fairly common dating — scholarly accounts I’ve read have had similar or even later dates for the occurrence [see Wikipedia, for example, for the OED date of 1909(!!) as well as some other potential dates.]

However, unless I’m missing something, most of this is wrong. The first mention found in newspapers is in 1863, not the 1870s, and it does not come out of court terminology, but rather politics. In fact it is used much as it would be today, to derisively refer to a set of allegedly less educated people who see a secret plot when a simple non-conspiratorial narrative has much more explanatory power.

One note here for people who haven’t delved much into the literature on this — conspiracy theory as a popular term doesn’t really take off until the late 1950s, and the scholarly concern about conspiracy theories (under a variety of names) gets its first significant lift in the 1930s and 40s in discussions about totalitarianism and populism. And of course conspiracy theories — under different names — have existed since the dawn of time. When we talk about early mentions we’re talking about the evolution of the term — the idea that you could have a theory that hinged on conspiracy, and how that would be regarded back then. This in turn plugs into a debate about how much our perception of such theories has shifted over time.

The Conspiracy of the British Elites Against the Union

So now we come to the first mention of “conspiracy theory” I’ve found, apparently missed by the OED and others. It will take a little explaining to set up. But it’s particularly surprising others have not found it since it’s from an exchange in the New York Times.

It’s from 1863, and it’s a response to a letter that had run the Sunday before. That letter had dealt with the question of why England — whose papers and elites had spent so much time attacking the United States over the institution of slavery in the 1850s — was now taking the side of the South in the Civil War.

The answer, the writer says, is obvious. America had been exerting influence on English institutions, and this had threatened the aristocracy, which feared loss of power. So they had embarked on a plan. They would support whatever side was weaker, in the hope that America would be destroyed. Once America was destroyed, then the governing classes could point to the failure of the U.S. as proof that democratic reforms don’t work, and reclaim power. In order to do this they would support the South verbally, but, importantly, not intervene on their behalf since the point is to avoid any decisive action that would hasten the conclusion of the war. Their best play was to draw out the conflict.

The ultimate endgame? Creating the “most terrible financial explosion ever seen in a civilized country” — all to benefit the small class of English aristocrats!

I am not a Civil War historian, so I can’t say if any of this was true. But in form it’s not terribly different from the conspiracy theories promoted by Sanders surrogates about the DNC, or theories tossed around the right wing blogosphere from time to time. Small set of elites that are afraid of the success of brilliant progressive/conservative ideas, and so what do they do — they sabotage them, just to say, hey I told you so.

Again — is it true? Who knows. But the form of the argument is very congruent with what we think of as conspiracy theorizing nowadays.

So the next week another person replies in the correspondence section of the NYT. And he says, look, you don’t need to invent this whole bizarre plot. England supported abolition when it was cheap for to them to do so. Now it’s looking like it might get expensive if their cotton is cut off, so they are muddling through this. Their lack of intervention is not due to a desire to let the war do maximum damage or cause financial collapse, but based on the fact that they have other foreign entanglements that are much more consequential at the moment and can’t afford a new one.

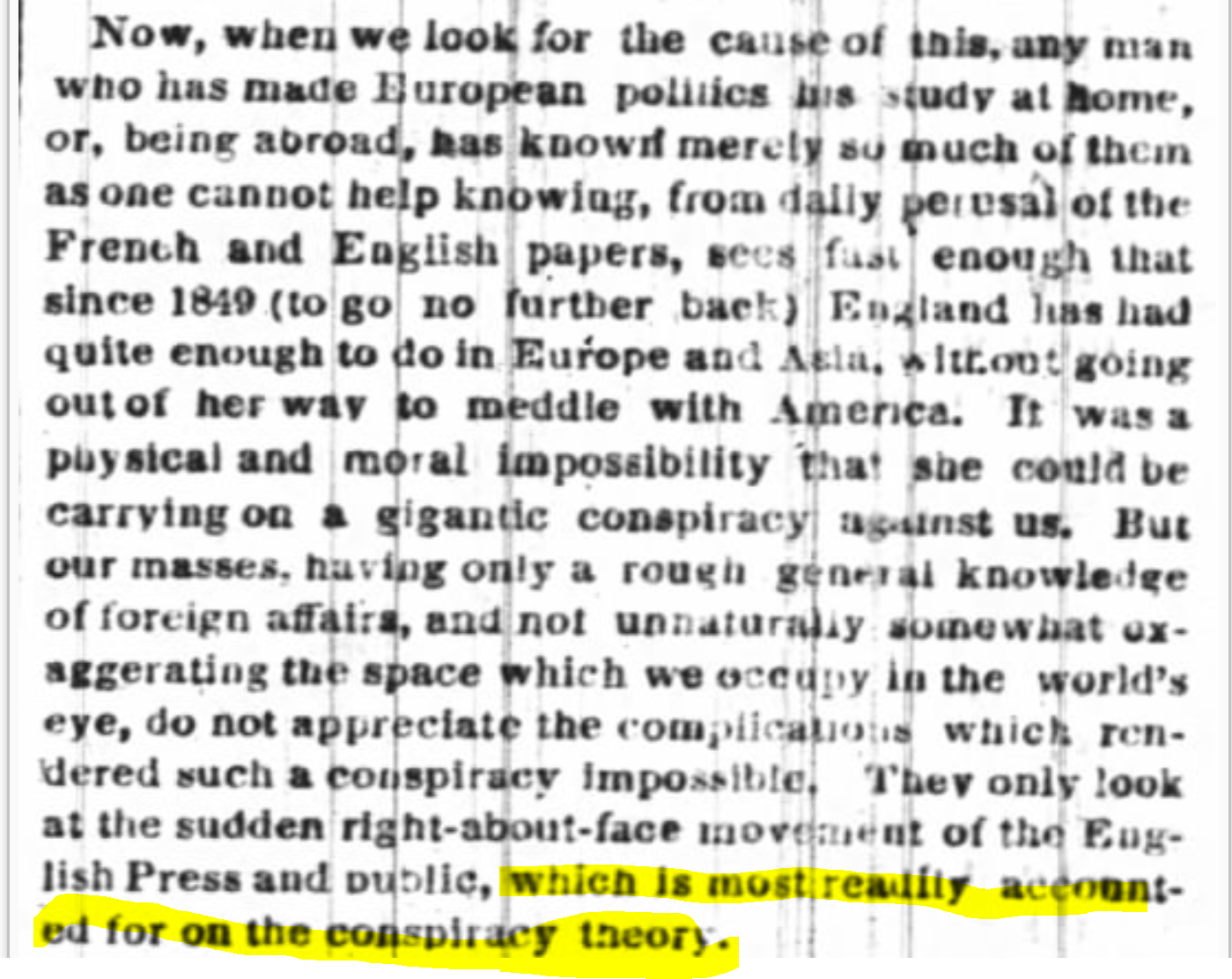

Here’s the text of the portion that mentions “conspiracy theory”:

Now, when we look for the cause of this, any man who has made European politics his study at home, or, being abroad has known mercily so much of them as one cannot help knowing, from dally perusal of the French and English papers, sees fast enough that since 1849 (to go no further back) England has had quite enough to do in Europe and Asia, without going out of her way to meddle with America. It was a physical and moral impossibility that she could be carrying on a gigantic conspiracy against us. But our masses, having only a rough general knowledge of foreign affairs, and not unnaturally somewhat exaggerating the space which we occupy in the world’s eye, do not appreciate the complications which rendered such a conspiracy impossible. They only look at the sudden right-about-face movement of the English Press and public, which is most readily accounted for on the conspiracy theory.

New York Times, January 11, 1863.

You’ll note here that conspiracy theory — almost ten years before the other examples historians often note — is used much how we would use it now. It’s a put down, an assertion that the complexity someone else sees is a result of ignorance or worse.

You’ll note too something that is almost too delicious: the first use of conspiracy theory is about a conspiracy said to involve the press . The first reference to conspiracy theory we have on record is, in part, a “The press is so unfair because they’re in the bag for the elite cabal” conspiracy. Fake news, man.

I can’t help but feel that this citation raises some questions — a few at least — around some of the cultural history I’ve read on the use of the term conspiracy theory. But it’s Christmas Eve, and I’m not really interested in those conversations right now — I just wanted to correct something I’ve been seeing people get wrong.

To my knowledge I’m the first to trace back the etymology this far, but if I’m not, you can let me know in the comments. If I’m not the the first, it’s worthwhile anyway to get this up so that people stop making this mistake.

Leave a comment